Unlock

Critical Thinking through

Reading and Writing

Our Literacy for Learning method is your roadmap to implementing the Science of Learning. By emphasising cognitive science principles, we reduce overwhelm and give educators a repeatable system that works across subjects and year levels.

Free: Guide to Building Critical Thinkers (Without A Million Activities)

The Real Reason Critical Thinking Isn't Sticking In Your Classroom - And What To Do Instead

Read our latest posts

Why the 'Great Mother Teacher' Myth Must Die

How gendered expectations are holding back teacher wellbeing, pay and student learning

Where are your boundaries? — They ask.

Boundaries? ... What's that? — Teachers collectively answer.

The photo below was taken in 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. I was on maternity leave, standing at my makeshift standing desk — a laptop stacked on boxes — conferencing with my Year 12 students while my six-week-old baby napped. The EAL teacher hired to replace me had quit, and my students were left with a string of casuals who, despite their best efforts, were out of their depth. I wasn’t being paid for this work, but I did it anyway.

My husband was (beyond) exasperated, and rightfully so. But the guilt and obligation I felt toward my students outweighed everything else, even my own newborn. I couldn't let them down.

Me teaching my Year 12s while on maternity leave 😬

Looking back, that image feels almost symbolic — a woman torn between her own child and her “school children,” believing that to be a good teacher meant to mother them all. But it’s not unique. It’s one of countless quiet moments that reveal how warped our expectations of teachers have become.

Educators, who are predominately women, are praised for their selflessness.

We wear the badge of martyrdom like part of the uniform. But the ideal of the 'Great-Mother-Teacher' — the endlessly nurturing, ever-patient figure who treats every student as her own child, plans meticulously, differentiates endlessly, gives emotionally, and asks for nothing in return — isn’t necessarily noble. It's arguably destructive.

This myth drives good teachers out of the profession. It erodes professional boundaries. But most importantly, it hurts the very students we’re trying to help.

On the surface, there seems to be nothing wrong with teachers acting like mothers — after all, aren’t we supposed to care, nurture, and build relationships? But this blurring of roles has profound consequences. It’s burning teachers out, damaging student outcomes, and undermining our ability to negotiate fair pay and conditions that could make the profession more sustainable.

IN THIS POST

Teaching is Not Motherhood: Why Blurring the Lines Can Fail Students

When the System Has No Boundaries

How the “Great Mother Teacher” Myth Undermines Evidence-Based Practice

Teaching is Not Motherhood: Why Blurring the Lines Can Fail Students

The myth of the “Great Mother Teacher” doesn’t just exhaust women, it confuses what good teaching actually is. When we believe that to be a good teacher means to mother every child, we risk replacing intellectual rigour with emotional caretaking.

Maybe it would all feel justified if it were truly what’s best for students, but I’m not sure it is.

A mother’s job is to provide comfort; a teacher’s job is to direct students into, and through, discomfort. When we conflate good teaching with making students feel good, we stop pushing them toward the productive struggle that real learning requires. Learning requires discomfort. It demands that students face challenge, confusion, even failure — and that teachers hold them there long enough to grow. True care in teaching isn’t shielding students from challenge; it’s giving them the intellectual tools to meet it.

Mothers are important, but they serve a different role to teachers

Some argue that without prioritising "caring" aspects, such as wellbeing, belonging and strong relationships, no learning can happen.

Let's unpack those claims.

First, research on motivation shows there’s more to learning than relationships and a sense of connection. Relationships matter, but so does competence and mastery — both of which depend on a teacher’s expertise, not their emotional labour.

Second, even if we accept that emotional and wellbeing support has a role in education, there’s a fine line between showing care and crossing into territory that isn’t ours. Most teachers aren’t psychologists or counsellors, and when we start taking on those roles, we risk doing more harm than good.

And third, we simply can’t do it all. When teachers are spread too thin, students lose out — not only on rigorous, consistent, high-quality instruction, but increasingly on the teachers themselves, who are leaving the profession altogether.

Just to be clear, I’m not suggesting that we shouldn’t have strong relationships with our students. But when we keep our primary role, teaching, front and centre, those relationships tend to form naturally. The time we spend inventing explicit “relationship-building” activities is time taken away from planning the kinds of intellectually rich lessons that foster genuine connection in the first place.

Teachers don’t need to manufacture care; it emerges through shared engagement in learning. One of my favourite memories of this came while teaching Animal Farm. I drew what was meant to be a pig on the board, only for my class to erupt in laughter. “That looks like a fat cow, Miss!” someone shouted. That moment, a shared laugh amid real intellectual work, did more for trust and connection than a month of circle time ever could.

Clearly a pig - What do you think?

When the System Has No Boundaries

Complicating all this is a system that doesn’t allow teachers to have boundaries.

In Victoria, for instance, schools are legally required to make “reasonable adjustments” for students — but what counts as unreasonable is not that clear, and often taboo to talk about. The result is a professional culture that discourages limits. No one tells a teacher to stop differentiating or to step back from giving endless emotional support, in fact school leaders might get in trouble if they encouraged teachers to pull back. The system itself has no stopping point, and so teachers internalise the same expectation.

Over time, the role of the teacher has expanded significantly. We are told that wellbeing is critical, belonging is critical, combating misogyny is critical, family engagement is critical — and, of course, so is maintaining academic rigour. We must support students with severe learning and behaviour difficulties while also extending those with exceptional ability, all within the same classroom.

Teachers are expected to fulfill many roles

In theory, these are noble goals. In practice, they create a job without limits. How can a teacher say, that’s not my role, when the system itself has blurred every boundary between teacher, parent, psychologist, and social worker?

We’ve become professionals expected to do the work of many but, when everything is important, nothing is important.

The truth is, mothers can never give up on their children, but teachers must sometimes draw that line. That’s not callousness; it’s professionalism. We have a duty to every student in our care, not just one or two who take a disproportionate share of our time and energy. Boundaries aren’t neglect; they’re a form of professional responsibility — to other students, to the system, and to ourselves.

I sometimes wonder if I used to justify my exhaustion by saying, “I’m doing it because I care so much about my students,” because the alternative — admitting that I had lost my boundaries, that I was stretched thin and neglecting my own life — would reveal the helpless position I was in. The system wasn't going to support me in setting those limits. But the ever-giving “teacher-as-mother” ideal doesn’t serve anyone. It produces burnt-out teachers and under-challenged students.

How the “Great Mother Teacher” Myth Undermines Evidence-Based Practice

The “Great Mother Teacher” ideal doesn’t just push teachers to do too much, it also shapes how we think about what good teaching is.

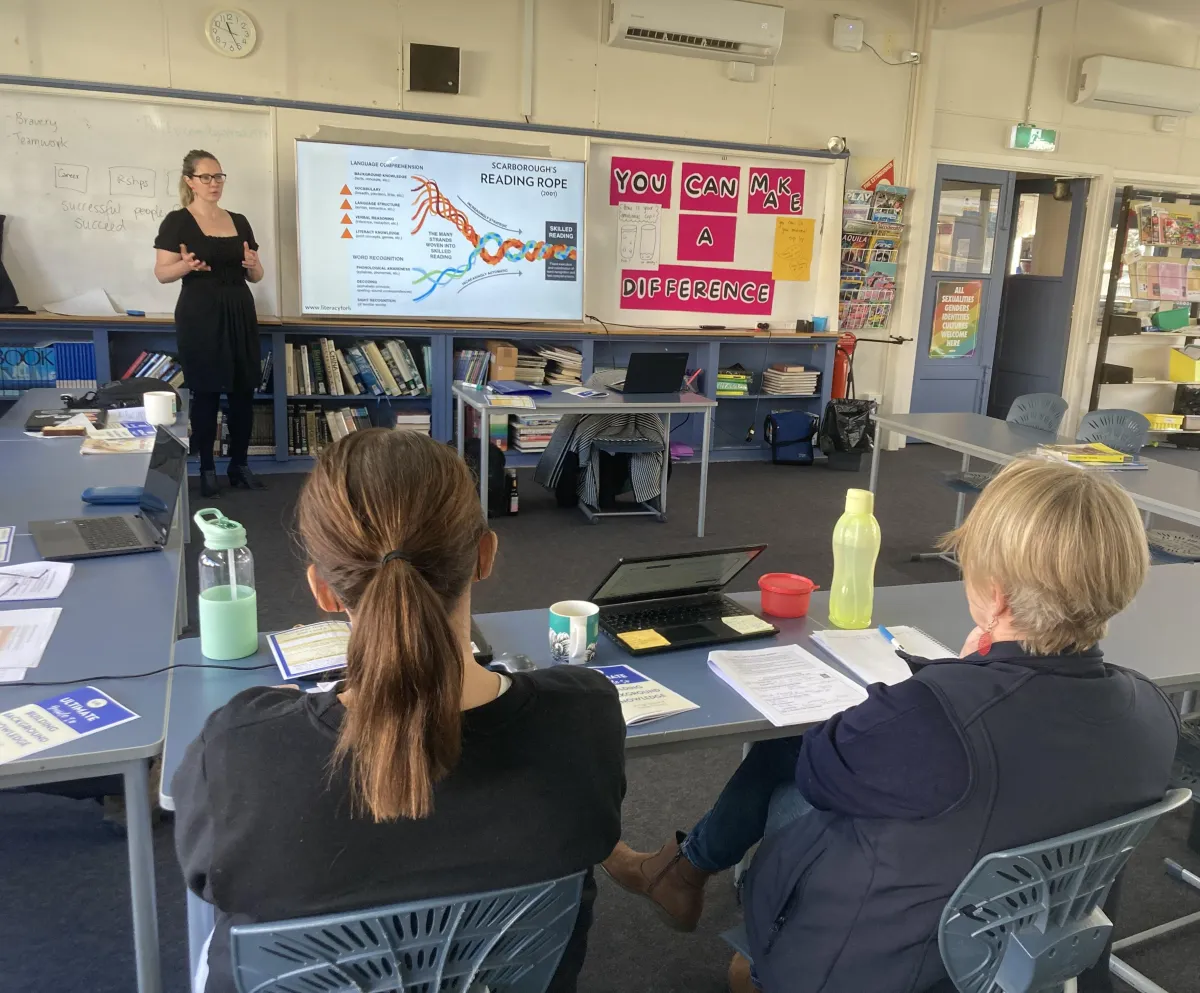

A year or so ago, I was presenting at a conference about the importance of knowledge instruction. The teachers were nodding, taking notes, clearly on board, until I used one phrase: rote learning. You could almost hear the collective recoil. It wasn’t that they rejected the evidence; they just couldn’t reconcile it with what they’d been taught a “good” teacher should be — warm, flexible, endlessly patient, building lessons around each child’s interests.

That moment revealed something deeper.

The “Great Mother Teacher” myth has quietly recast our professional identity. It encourages empathy over expertise, relationships over rigour, and feelings over knowledge, as though intellectual leadership and care in teaching were opposites.

Teacher-led, explicit instruction is rejected by many teachers as “authoritarian” and old-fashioned

I heard a similar sentiment recently at Pilates. A woman who had taught primary school for thirty years told me she quit because “it’s not about the kids anymore — it’s all about the test scores.” I understood her frustration, I strongly feel that we are over-using and misusing data. But her statement demonstrated a common misconception about the science of learning. Evidence-based teaching isn't about data for its own sake. It’s about checking in with students to see where they are in their journey to acquire the knowledge they need to think, question, and understand. And that, most definitely, is “about the kids.”

Decades of cognitive science are clear: students learn best when teachers guide them systematically through content, ensuring mastery before moving on. Explicit instruction, well-sequenced curricula, and teacher-led lessons aren’t relics of an authoritarian past, they're the most reliable ways to help students succeed, especially those who start behind.

When we elevate “care” above “expertise,” we don’t just exhaust teachers, we deprive students of the very thing that would empower them most: knowledge.

Mothers Aren't Paid - So Why Should Teachers?

Do you know what else happens to mothers? They don’t get paid.

In my first school, the principal decided to remove the small payments for extra responsibilities — like Year Level Coordinator. These were barely symbolic, maybe $2,000 a year, but they recognised the extra work teachers did. When staff pushed back, the principal’s response captured the wider sentiment: “If you’re doing it for the money, you’re doing it for the wrong reasons.”

That moment illustrates the problem. This wasn’t just about $2,000, it was about how deeply the “mothering” narrative has infiltrated our profession. We're expected to give endlessly, to do the work “for love,” not for fair compensation. But love doesn’t pay rent — and “working for love” drives good teachers out of the system.

Many who leave tell me the same thing: I can get paid more, have greater flexibility, and work less elsewhere. I can’t justify going back.

This Mother-Teacher Myth also shapes how we think about industrial negotiations. In a recent pay discussion, I told a male colleague that for me, it wasn’t about money — it was about time. His response is what ultimately led to this blog post: “That’s such a female thing to prioritise.” He was right. What I was really saying was, I’m willing to earn less if it means giving more of myself to students — because that feels morally right.

As the Victoria’s teachers’ agreement is renegotiated, this myth continues to cast a shadow. The idea that “you’re not in it for the money” undermines our bargaining power.

Of course, I’m not suggesting teachers should never give their time freely. I wouldn’t want to miss the magic of school camps, valedictory dinners, or student productions, those are some of the moments that make teaching meaningful.

In most professions however, staying late earns flexibility — leave early, work from home, adjust hours. In teaching, that flexibility rarely exists. I once had 15 minutes docked from my pay for being late, despite not teaching first period and always staying late. We all saw how many issues trying to formalise “time in lieu” caused in Victoria. Perhaps what teachers need isn’t more red tape — it’s professional trust and autonomy.

Reclaiming the Core Purpose of Teaching

So where do we go from here?

We need to let go of the myth that being a good teacher means being everything to everyone — the parent, counsellor, nurse, social worker. It doesn’t.

The most powerful thing we can do for our students is teach them well. That means evidence-based instruction, a clear, coherent curriculum, and systematically building knowledge and skills systematically over time — not scrambling to design disconnected activities in the name of engagement or wellbeing.

Our students already have parents. And while some may not have the level of support we wish they did, trying to fill that role ourselves doesn’t fix the problem, it compounds it. What truly changes a child’s trajectory is not more “care” in the emotional sense, but the empowerment that comes from learning. The ability to read, reason, and make sense of the world — these are the tools that allow our students to break cycles of disadvantage and trauma.

The system needs to clearly define the role of the teacher so that we can feel confident in saying 'no, that's not my role'

Above all, as the Victorian teachers’ agreement is renegotiated, we must push for systemic change: protected planning time, realistic expectations around differentiation and student accommodations, and clear boundaries that keep the focus on our core work, teaching and learning.

Teaching can be joyful and sustainable. But only if we reclaim our time, our expertise, and our purpose.

The “Great Mother Teacher” ideal must die. Not because care isn’t important, but because it’s drawing focus away from our primary role.

We are not parents. We are educators. And when we are allowed to do that job well, we change lives.

It’s time to stop chasing the myth — and start demanding a system that prioritises what we actually do.

Join a community of teachers getting research-backed insights in their inbox each week

We'd love to have you :)

Frequently Asked Question

General Questions

How does the L4L process work?

The Literacy for Learning (L4L) process is a streamlined system built on principles of cognitive science, in particular the elements of Scarborough’s Reading Rope and Cognitive Load Theory. It’s designed to take the guesswork out of lesson planning and equip teachers with a clear, practical framework for creating rigorous, knowledge-rich lessons. The process starts by grounding teachers in the foundational knowledge about how students learn best. From there, we provide simple, actionable strategies to build students’ schema and critical thinking through reading and writing—without relying on fads or overwhelming amounts of resources. With a focus on explicit instruction and structured planning, the L4L process helps teachers implement these principles confidently and consistently.

What makes your professional learning and support unique and effective?

What sets L4L apart is that it is a holistic planning and teaching system rather than pre-made resources or a bunch of teaching strategies. Our approach bridges the gap between theory and practice, breaking down complex cognitive science principles into a teaching model that is easy to understand and implement in the classroom. We also offer ongoing support, fostering a sense of community where teachers can share their successes and challenges. This personalised guidance ensures that teachers not only learn the method but also adapt it to their unique contexts, making the learning truly transformative.

What outcome can teachers expect from the L4L professional learning and resources?

When you work with us, you can expect to feel empowered and confident in your teaching. You’ll gain a deeper understanding of how students learn and how to create lessons that maximize engagement and impact. This transformation isn’t just about improving your students’ outcomes—it’s about simplifying your workload and giving you clarity in your teaching practice. By focusing on what truly works, you’ll save time, reduce overwhelm, and experience fulfillment knowing you’re making a lasting difference in your students’ lives.

Who is an ideal candidate for the L4L professional learning community?

The ideal candidate for the L4L professional learning community is a teacher who’s passionate about delivering high-quality education and is ready to embrace a rigorous, knowledge-rich approach. Whether you’re feeling overwhelmed by conflicting teaching strategies or simply looking for a more effective way to engage your students, this community is for you. It’s particularly valuable for educators who want to prioritise explicit instruction, build their students’ critical thinking skills, and feel confident in their ability to simplify and implement the science of learning in their classrooms.

Why is learning some of the science so important when it comes to teaching?

Teaching is one of the most important jobs in the world, but it’s also incredibly complex. Understanding some of the science behind how students learn—like how knowledge builds on prior knowledge or how memory functions—gives teachers a powerful advantage. Without this foundation, it’s easy to rely on trends or surface-level strategies that may not truly support student growth. Learning the science empowers teachers to make evidence-based decisions, create lessons that stick, and build the schemas for critical thinking that change lives. It’s about teaching with intention and confidence, knowing you’re giving your students the best possible foundation for their futures.

Empowering teachers to implement the Science of Learning

Links

Home

About Us

Blog

Newsletter

Join our community to stay updated on the latest courses, exclusive content, and learning resources.